Emile Zola was a French journalist whose article J'Accuse was of major importance in France at the end of the 19th Century, regarding the prosecution of an alleged army spy Alfred Dreyfus. His piece of work concerning this affair is a shining example to journalists regarding their power to shine light upon injustice.

Before explaining the affair itself, allow me to summarize the context of the time;

A number of years of tension between the French Empire and Prussia along with the other Germany states, culminated in the Franco-Prussian War in July 1870. The Battle of Sedan in Septmember 1870 was a comprehensive victory for Prussia and led to the eventual surrender of the French in May 1871.

After winning the war Prussia led a siege on Paris, forcing the provisional French government of the time to sign a humiliating treaty in Versailles, later known as the Treaty of Frankfurt. This forced France to pay huge war reparations and give up the Alsace-Lorraine territory to the soon to be unified Germany. To further add to the embarrassment Prussia would hold victory celebrations in Paris.

After Prussia had left France, the ordinary working class, fed up with the weak provisional government and sick of the high rent imposed upon them by their wealthy landlords led to a revolt in Paris - eventually leading to the establishment of the Paris Commune on March 18th 1871. The commune set up was based on socialist values; allowing workers to run businesses, the separation of church and state, the abolishment of night work and was also feminist sympathetic.

This 'communista' scared the French army and royalists - as well as much of Europe as it echoed many of Karl Marx's work and highlighted the 'spectre haunting Europe - the spectre of Communism'.

As a result of this the French Army decided to tear apart the commune. They flooded Paris and ruthlessly destroyed many working class areas - killing between 20-30,000 including women and children - although some suggest the death toll was actually higher! The Commune was effectively obsolete as of May 28th 1871.

It was short lived, but had a massive effective on European politics.

Now back to Zola and The Dreyfus Affair:

Following the humiliation of the Franco-Prussian War and Paris Commune France was in a 'hangover' state, with national identity at a low. Revenge against Germany became an obsession and they tried to build up respect again by creating an overseas Empire. particularly in Africa.

There was also a need to blame someone for the previous failures. There were many rumours of traitors in the army and much of the blame was laid on the Jews. This was furthered still when a business scandal at the Panama Canal showed certain Jewish businessmen had been taking bribes - Anti Semitism in France was flamed.

When important documents were discovered in the German embassy the France Army needed to find a scapegoat. Alfred Dreyfus was an intelligent and highly capable French Army captain, but as a Jew (in addition to hailing from the Alsace-Lorraine region) he fitted the bill for scapegoat perfectly.

The Army held a secret Court Marshall, finding him guilty of treason (despite bringing forward no evidence), stripping Dreyfus of his medals and exiling him to 'Devils Island' where he suffered all manner of neglect and cruelties.

An officer later looking into the case actually found evidence that a different man named Esterhazy was actually the guilty culprit - as his handwriting matched that found in the German Embassy, however despite the overwhelming evidence Esterhazy was acquitted in order for the Army to save face.

The trial was attended by French writer Emile Zola. On January 13th 1898 Zola published an open letter to the French President entitled 'J'Accuse' (I accuse).

Zola begins by paying his respects to the President - although he insinuates that history will remember who was in charge overall when re-visiting the Dreyfus Affair, which he describes as a stain on any French achievements. Zola describes the decision to acquit Esterhazy as a 'great blow to all truth' and effectively uses emotive writing throughout the piece to stress the importance of justice.

Zola dares to openly criticise those responsible for the cover up in the letter - stating that it is his 'duty to speak'. I think that this is something all journalists could learn from, we are effectively the eyes and ears of the public and as such I feel that there should be a large degree of honesty in our work - though this is clearly not always to case.

Zola sarcastically lists Dreyfus' ''crimes'' of being too ambitious, bright, calm and nervous. He uses this juxtaposition at the end to highlight the ridiculousness of the charges and to stress the unfairness of it all. Zola highlights the guilt of the officers who covered it up - ''they close mouths by disturbing hearts, by perverting spirits''. Zola considers this the greatest crime, showing that he was a keen believer in freedom of speech.

Zola outs those concerned with the wrongful framing of Dreyfus as anti Semites and adds that ''when society does this it falls into decay''. This shows signs of the desire for equality that the Paris Commune had potentially opened the doors for previously.

Zola criticises the media coverage of the trial. They, like him, must surely have seen the evidence and realised Dreyfus' innocence and yet chose to ignore this. He blames them for misleading the public and effectively fuelling bigotry. Zola emphasizes this by saying ''it is a crime to poison the small and humble, to exasperate passions of intolerance, a crime to exploit patriotism for hatred'' and adds ''if not cured France's liberal human rights will die''. This highlights the affect that the media can have in influencing the minds of the public - Zola is bluntly critical of the French media for promoting hatred of Dreyfus and Jewish citizens through their writing and by saying that France's liberal rights will die if this continues he is recalling the French revolution and its original cries for freedom.

Perhaps the most important part and J'Accuse is the conclusion. Zola clearly states the list of people who he blames for the wrong-doing in the Dreyfus Affair and gives his reasons why. The format of the text is laid out clearly in a list form so that Zola's accusations are blatent for all to see. Also Zola does not list Esterhazy in his accusations perhaps showing his obvious guilt by saying it isn't even worth exposing. He could also be highlighting the injustice committed by the state, showing that this was the worst crime.

Zola admits that he is aware of the trouble he may get in for doing so and acknowledges that he is potentially being libellous and guilty of slander. This is incredibly brave journalism, putting himself in the firing line in order to report truthfully and Zola's passion is clearly something to aspire to - he's something of a Saint or Superhero of journalism. The fact that this article led to him being convicted of libel and sentenced to prison before he managed to flee to London only enhances this reputation.

Zola saw his article as a catalyst for truth. His bravery could be seen to have been rewarded in that Dreyfus was awarded a secondary trial and despite being found guilty again this time there was massive outcry against the decision and he was eventually exonerated in 1906 after being pardoned four years earlier - although he was now a broken man.

When Zola died he was taken to the Pantheon to be buried, with Dreyfus present at the ceremony (where there was an assassination attempt of him!). I think that Zola deserved the accolade of being buried there as his work for justice and free speech in spite of a hostile situation is a noble cause and something that all journalists and writers should aspire to. Hero.

Josh Tyler

Wednesday 18 May 2011

Monday 9 May 2011

Super Injunction Superhero - Twitter user lists Injunction ''Celebrities''

Twitter user @Injunction Super has thrown a massive spanner in the carefully created machine of celebrity super injunctions by revealing the names of people who have recently taken out injunctions and listed the 'crimes' that they were so keen to hide.

These allegations include the premier league family man who had a six month affair with former Big Brother babe Imogen Thomas (though why he wanted to keep that secret is beyond me - I would've told anyone who'd listen), as well as other personal stories concerning some Z listeners that should be glad of the publicity.

Whether or not the user could be sued for libel or defamation remains to be seen, as this is effectively a ground breaking story - and one that highlights the ever increasing change that social networking sites are having on journalism. The papers are surely loving this development - the red tops will surely now be able to print the sexy pictures and stories of fame hungry home wreckers and the qualities will surely be able to write about their own brand of smut by criticising Andrew Marr - though I pray there wasn't a sex tape involved in his affair.

Whether or not the user could be sued for libel or defamation remains to be seen, as this is effectively a ground breaking story - and one that highlights the ever increasing change that social networking sites are having on journalism. The papers are surely loving this development - the red tops will surely now be able to print the sexy pictures and stories of fame hungry home wreckers and the qualities will surely be able to write about their own brand of smut by criticising Andrew Marr - though I pray there wasn't a sex tape involved in his affair.

Should we care about the private lives of these people? Probably not.

Will the recent media backlash against super injunctions benefit from this masked crusader? Probably.

Is this yet another example of how social networking is changing the face of Journalism? Definitely.

And whilst your @ it (see what I did there) follow me on http://twitter.com/#!/joshyboytyler - ignore the shameless attempts for a retweet - I might be a good journalist one day...

Will the recent media backlash against super injunctions benefit from this masked crusader? Probably.

Is this yet another example of how social networking is changing the face of Journalism? Definitely.

And whilst your @ it (see what I did there) follow me on http://twitter.com/#!/joshyboytyler - ignore the shameless attempts for a retweet - I might be a good journalist one day...

Tuesday 3 May 2011

William Cobbett's Rural Rides - Seminar Notes

William Cobbett was born in 1763 in a rural area of Surrey. He spent 15 years in the army however his discovery that a senior officer was stealing army funds led to him being branded a trouble maker and he subsequently moved to France. On returning to England Cobbett started a Conservative newspaper ‘The Political Register’ in 1802 however he gradually began calling for more political reform and swayed towards the more radical movement. Cobbett’s views led to him spending two years in prison and he caused great opinion amongst the rich which we see in Rural Rides in regards to the many people who he lists as speaking unfavourably of him.

Rural Rides has a somewhat typically English start by mentioning the weather in the opening sentence ‘I set off, in rather a drizzling rain’.

Rural Rides has a somewhat typically English start by mentioning the weather in the opening sentence ‘I set off, in rather a drizzling rain’.

Cobbett set out to experience the countryside particularly farming areas – this could be as the industrial revolution was beginning and as a result farms and the country were perhaps becoming forgotten or deprioritised.

He is critical of those who are living of government hand outs under the poor laws of the time saying they have ‘every appearance of drinking gin’ and he may be suggesting that many of them are doing themselves no favours to improve their situation.

He mentions how at the Horse Fair cart colts are selling for less than a third of what they were 9 years before – I think that this could again show that perhaps the old methods of farming are beginning to be phased out and made redundant as machines became more prominent.

The Mr. Fox affair which Cobbett describes is critical of those in power, particularly Fox and implies that there was much greed and corruption amongst land owners which was unfair on the general public. Cobbett firmly outlines this in saying ‘such are the facts’ before inviting us to draw our own conclusion – something of a rhetorical question.

Cobbett calls for more political courage from landowners and politicians – he believes that many of them prevent reform and improvement by dismissing every new idea or reformer as ‘Jacobin’.

He blames lack of reform for ‘loan jobbers’, ‘stock jobbers’ and Jews gaining estates – Cobbett himself was anti-sematic.

Upon entering Chilworth Cobbett describes excellent farming conditions and the potential value of goods at market with great detail. As he was from a rural area himself and worked as a farm labourer as a young man he clearly has great nostalgia about the countryside – it could perhaps be suggested that ‘blind nostalgia’ is his main motive behind his criticisms of industrialisation. The embodiment of this nostalgia could be seen in his great love and admiration of the English oak tree.

Cobbett describes the public as the ‘generous landlord’ and implies that the rich themselves are not generous – that is why they remain rich. He calls for a reformed parliament in order to manage the public’s affairs better, though he seems to have little faith that this will happen as the ‘snug corporations’ and rich tenants tend to be the politicians as well and therefore it is in their interests to keep the poor, poor.

Upon entering Winchester Cobbett says that amongst labouring people the first thing to look for is honesty. This however, is something that cannot be expected of them unless their bellys are full and they are free from fear – this must come however from them earning wages and not from government hand outs. Cobbett again calls for the powerful to use their influence to prevent wage diminution of labourers – to be politically brave and call for reform.

In Winchester Cobbett has a dinner meeting with some of the local farmers. He says that the wealth of the church – and the wealth it bestows upon its ministers, in addition to the relief the government gives to the poor clergy despite the churches wealth is a clear example of why the current system must be reformed and changed.

Cobbett calls on the middle classes to aid the poor in taking the lead in demanding parliamentary reform.

Cobbett is also critical of the new barracks and houses that sprang up on his travels. He felt that they were not created out of a desire to help the poor and were not paid for by money – but created by labour – and the labourers were not appropriately rewarded for their efforts.

Cobbett describes the kindness that he is shown in Reading in particular and I think that this may well show that there is a certain union among the people in that they agree with many of his beliefs. This kindness is given despite the government and land owners determination to keep Cobbett out of parliament and to keep him down and this was something that seemed to spur Cobbett on throughout his travels.

Cobbett has clear dislike of taxes and this is shown when he hires a man to guide him from Hampshire into Surrey ensuring that he avoided the turnpike at Hindhead – as to use this he would have been taxed. However, the guide got lost and Cobbett ended up having to pay the tax – though he refused to pay the guide – showing again that he had a disregard for charity and felt that wages should be earnt.

Cobbett was also clearly opposed to those in beaurocratic jobs – who he calls tax eaters. This is something that is perhaps still relevant today – with many local councils and civil servants losing or having their jobs readjusted in the government cuts.

Cobbetts criticism of the Corn Laws which came in in 1815 are clear throughout the book. He seemed to suggest that this created farmers who became gentleman and as a result their workers became more like slaves. The initiative to ‘Buy British’ that the Corn Laws created meant that there was overproduction of goods in some years, despite the expanding population – as a result of this prices of crops were forced down and therefore farmers made less money than before – Cobbett is critical of this as it widen the gap between the rich and the poor.

Cobbett outlines his belief that the old system was better than the new, industrialisation whilst journeying towards Bath, when he says that ‘any man of sense feels our inferiority to his fathers’. I feel that in this aspect Cobbett is somewhat short sighted with regards to industrialisation. He appears to not see it as beneficial in any way and with hindsight I would argue that it brought many great inventions and even wealth to the British Empire – though Cobbett’s calls for this wealth to be more evenly and fairly distributed given the poverty many endured during this time is of course a very valid point.

In Tutbury Cobbett describes meeting a man who asks if he has seen a poor old man – as he is wanted for stealing cabbages from a landowners’ garden. Cobbett’s anger that this poor old man is wanted for this shows consistency with his earlier sentiment that you cannot expect a poor man to be honest if he is starving. This is an example of the consistency of opinion that Cobbett shows throughout Rural Rides and I think that to his credit he shows little or no hypocrisy of opinion throughout the book.

Cobbett shows a great sympathy and respect towards the Irish. He criticises those who are against Irish immigrants as he believes that they are a people willing to work. He instead describes the Scotch as ‘tax eaters’ (perhaps in retaliation to those whose call him a Jacobin).

Cobbett finishes his travel guide by praising the benefits of sobriety, early rising and firm resolution – something that he claims to have shown throughout his trip. This is effectively a summary of his belief in a hard-working, agricultural Britain, where such efforts and labours are rewarded.

Overall, figures such as Charles Dicken’s work and effect on British cities are perhaps better remembered, though no more valiant than Cobbett’s in the countryside. I would argue that this was perhaps Dicken’s created much more exciting and enjoyable stories. Cobbett’s journey in Rural Rides was clearly an eventful one with many hardships and astute observations made along the way however, I found it slightly tedious and his obsession with the quality of the soil and tendency to waffle on are perhaps the main reason why the book is not as widely heard of as many of Dickens’ works. It could be argued that Cobbett was trying to take things back through his reforms whereas Dickens sought to move forward – Cobbett fondness for nostalgia certainly suggests this, As well as this Dickens wrote about an expanding population in the cities, whereas Cobbett was appealing and writing about those in the countryside – an increasingly emptying area.

Cobbett could perhaps be compared in some ways to Darwin. Darwin was a great believer in travel and exploring the world for himself enabled him to form his theories on evolution. Similarly Cobbett should be praised for getting amongst the problems in the countryside and experiencing them for themselves in order to formulate his opinions and solutions. This notion that we learn through experience is also present in the theories of Locke’s Tabula rasa and much of the Empiricist movement – though his love of the countryside also mirrors Rousseau’s love of nature.

Wednesday 27 April 2011

Radio Script

1. Unemployment:

Almost one million young people are unemployed, the latest national office figures have announced. The number of jobless 16-24 year olds lept by 66,000 in the three months of 2010 - the biggest unemployment slump since World War Two.

Of the 210,000 jobs created by the government last year, 82% were given to people born outside of the UK, mainly those from Eastern European nations.

End time: 0'26

2. Beggars:

The number of beggars in Winchester City Centre that are acting as buskers to get around County laws, is becoming a major problem. We spoke to PCSO Helen Carthew:

Audio clip Helen Carthew 0'25

3. Social Care:

Plans to increase the maximum weekly expensive for adults requiring domestic social care to 100% of their net income have been rejected by Hampshire County Council. The maximum charge will now remain at 95%. Similarly a proposal to charge the carers themselves was also rejected after a survey showed 75% of the public disagreed.

Almost one million young people are unemployed, the latest national office figures have announced. The number of jobless 16-24 year olds lept by 66,000 in the three months of 2010 - the biggest unemployment slump since World War Two.

Of the 210,000 jobs created by the government last year, 82% were given to people born outside of the UK, mainly those from Eastern European nations.

End time: 0'26

2. Beggars:

The number of beggars in Winchester City Centre that are acting as buskers to get around County laws, is becoming a major problem. We spoke to PCSO Helen Carthew:

Audio clip Helen Carthew 0'25

3. Social Care:

Plans to increase the maximum weekly expensive for adults requiring domestic social care to 100% of their net income have been rejected by Hampshire County Council. The maximum charge will now remain at 95%. Similarly a proposal to charge the carers themselves was also rejected after a survey showed 75% of the public disagreed.

Tuesday 5 April 2011

Radio News Bulletin

Here's the youtube link for my Radio News Bulletin, featuring reports on young unemployment levels, Winchester's problems with beggars and news on the Council's proposals to change its social benefit system.

Due to my technological ineptitude I also have one other story on the Winchester Tourism Boards nomination for a National award, which I will try to put up as soon as I can.

To hear the bulletin visit http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JMyPhWWMuEw

Due to my technological ineptitude I also have one other story on the Winchester Tourism Boards nomination for a National award, which I will try to put up as soon as I can.

To hear the bulletin visit http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JMyPhWWMuEw

Sunday 20 March 2011

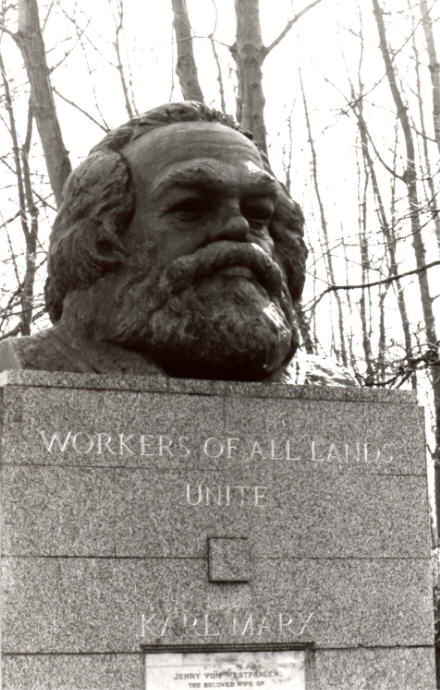

Karl Marx

Karl Marx, 1818 - 1883 was a German philosopher and political theorist who is considered the father of Communism.

Karl Marx, 1818 - 1883 was a German philosopher and political theorist who is considered the father of Communism.Marx originally studied law and then philosophy before becoming interested in revolution. He was a journalist and editor for many radical newspapers across Europe, however his revolutionary ideas led to him being forced out of many countries before he settled in London, where he stayed until his death.

Marx believed that his approach to politics was economical and scientific. He thought that you could explain everything by analysing the way economic forces society in social, religious, legal and political processes. Marx's friend and the co-author of The Communist Manifesto Fredrich Engles believed that Marx achieved a fusion of Hegelian philosophy, British Empirical economics and French revolutionary politics, particularly the socialism aspect. Marx himself linked much of his work to that of Charles Darwin, however Darwin himself is said to disputed this.

Many of Marx's theories appear to have been influenced by Hegel, though he dismissed and changed many of Hegel's ideas. The Hegelian theory of the dialectic is clearly the one with which Marx is most concerned with. As I have previously explained http://josh-tyler.blogspot.com/2011/03/georg-wilhelm-friedrich-hegel.html, Hegel felt that change occurred when one idea (the thesis) was contradicted by another (the antithesis) to create a new idea - the synthesis. Marx liked this idea as a way for history to progress, however, whereas Hegel believed that history was guided by a 'geist' spirit towards an absolute end, Marx believed it was more practical and political, dismissing Hegel's idea as idealist nonsense.

Marx saw the real dialectic not as a geist, but in economic life, particularly in class struggle. His theory of history is therefore known as 'Dialectic Materialism'. Indeed in changing Hegel's key philosophy (as well as disagreeing with his love of the state and belief in God) Marx demonstrates his belief in using other ideas as only an outline to create your own: 'the philosophers have only interpreted the world - the point however, is to change it'.

The idea of class struggle is the main driving force of the Communist Manifesto. Marx outlined that society was now separated into two classes; the working Proletariat and the Bourgeois. He believed that though the Bourgeois were in themselves a revolutionary force, they did so solely for capital and greed, turning all professionals into mere paid wage labourers. He criticised globalisation and industrialisation for placing property and ownership into just a few wealthy hands and as a result creating political centralisation of power.

This society, with all its new machinery and processes reduced the lower middle class to working class and as a result united the low paid worker, creating a more unified Proletariat. Marx actually has 'workers of the world, unite' on his tombstone. Marx felt that this was a clear example that capitalist society and the Bourgeois who created it were doomed to fail and were simply 'digging their own graves'. As the Proletariat had nothing to lose and everything to gain, it was they who could act as the antitheses of the dialectic and drive change in, Marx saw this change as socialism and eventually Communism. Marx envisioned this as a society of equality, justice and the fulfilment of a truly free individual.

Marx outlines in The Communist Manifesto ten main policies that the Communist party would enforce;

1. Abolition of Private Property

2. A heavy graduated income tax

3. Abolition of inheritance right

4. Confiscation of rebel and emigrant property

5. Centralisation of banks

6. Centralisation of transport

7. Extension of factories

8. Combine agriculture with manufacture (to establish a more balanced difference between cities and countryside)

9. Equal obligation of all to work

10. Free education for all children and abolition of child labour.

Once this measures were in place Marx believed that class distinctions would disappear and the public would lose its political character. This would mean that the dictatorship of the proletariat (a socialist process that Marx felt was necessary for the laws to be implemented) would become redundant.

After this a free and equal society would prevail, a society where man was not alienated from one another, were we value each other over gain and possessions and behaved From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.

The manifesto ends with a Rousseau inspired slogan to encourage the working class to rise up and end the oppression of the Bourgeois:

Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communist revolution. The proletarians having nothing to lose but their chains.

Wednesday 9 March 2011

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Hegel was a German philosopher who lived from 1770 to 1831 and is often credited as the culmination of the German idealist movement that began with Kant.

Hegel had a belief in the unreality of separate parts. He felt that nothing was completely real except the 'whole' and saw everything as a complex system that could only be considered when seen as a whole. He felt that 'whatever is, is right'. Hegel refers to the whole as the 'absolute' and considers it spiritual. As a result of this it appears that God is the absolute, a pure being.

Hegel's view on spirituality is an interesting one, that comes from his idea of the 'dialectic'. Hegel believed that everything had a thesis (a proposition) and an antithesis (contradictions to this). The result of these two ideas led to the Synthesis - a combination of opposing points of view that in turn created a new idea. When linking this to his idea of spirituality, Hegel believed that we as humans moved towards the 'absolute, pure being' (God) through a series of dialectic transitions. He referred to these periods of transition as 'geists' and suggested that these were guided by an external force rather than through our own actions. Hegel believed that we will become an absolute being once we have self knowledge of our spirit.

Hegel's political views were also based upon his dialectic theory. He thought that world history repeated the transitions of the dialectic and that it too was guided by a geist in moving towards an eventual end. Using War, for example helps to explain Hegel's theory. If we consider one nation as the thesis and one as the antithesis, the result of the conflict would be the synthesis - and this is how change occurs throughout history.

Hegel was a great lover of change however there does appear to be some contradictions in his own political beliefs. In his later life he was very pro-German, however he was also a great supporter of Napoleon and was said to have welcomed his defeat of the Prussian army.

Hegel's glorification of the state in his later life could also be seen as a contradiction. He felt he was a great lover of change and freedom, however he also felt that there was more freedom to be found in a monarchist rule than in a democracy. This would suggest that he was both a lover of freedom and obeying the law, Bertrand Russell describes this contradiction perfectly by arguing that what Hegel really believed in was 'the freedom to obey'.

Hegel's theory leads nicely on to my next History and Context of Journalism study - that of Karl Marx. Marx's relationship with Hegel's theories appears to be an interesting on, with Marx dismissing Hegel's views on the hidden geists as idealist nonsense, but appearing to agree with Hegel's theory of the dialectic as a process to drive change and he perhaps applied this theory in a much more realistic and empirical way than the ideals of Hegel .

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)